If Anna Bolena updated the dramatic characters of an opera seria, L’elisir d’amore – a comic and rustic rendering of the Tristan and Isolde tale, redefines the elements of the “commedia buffa” of the eighteenth century, giving birth to a new terminology. Thus, the specification of “melodramma giocoso” of Elisir acquires its meaning in the moving, pathetic and elegiac smile that perfectly counterbalances the “buffo” laughter of the classic comic opera. And Donizetti pushed this semantic subtlety of the words even further when he called Don Pasquale a “drama buffo”.

Opera di Firenze. Cortile di palazzo Pitti. Prove generali dell’ opera “L’elisir d’amore”.

Apparently Elisir features characters that have been already exploited and even abused. Nemorino is the village idiot, ready to swallow, both literarily and figuratively, Tristan’s fairy tale; Dulcamara is the typical charlatan, and Belcore is the classic blustering and swaggering soldier going all the way back to Plautus’ “miles gloriosus”. Adina is the flirt, the girl who can read and write and looks down on the peasants. Modern psychology would consider her as the quintessential example of a narcissistic personality who believes that that everything is owed to her and who gets irritated if she realises that people in whom she is not interested are not interested in her: it is an easy guess that the union between a professional manipulator and a “beta” male (and some doubts about his virility come from the bassoon in the introduction to “Una furtiva lagrima”, an instrument that like the cor anglais and the clarinet were usually associated with female characters) with serious self-esteem problems is not destined to have a happy end. In any case the disparity between these four characters and their respective “maschere” of opera buffa is abysmal: the latter are epigones following a pre-determined model, while the former are perceived by Donizetti like eponyms into whose humanity idyll and gossip, scratches and sighs, cunning and naivety miraculously weave together. Donizetti uses sophisticated musical tools to highlight Nemorino’s sincerity in opposition to the simulation, the artifice and deceit of the others; already in the initial cavatina “Quanto è bella, quanto è cara”, apparently just a simple Larghetto in C major, it is easy to detect inflection in minor mode (first E minor and then C minor), true presentation cards of the melancholy and sentimental personality of the character, who, among other things in characterised by the tendency to express himself in flat keys, rather uncommon for a buffo character. The other three entrances are parodies: Adina, introduced with a waltz and a mazurka, does not believe at all in the existence of Isolde’s philtre; everything about Belcore’s military-style rhythms and pompous coloratura speak of exaggeration and braggadocio. The peak of lie and deceit takes place in Dulcamara’s cavatina, where – as it has often been remarked – the insisted use of proparoxytones (normally used in relation to supernatural entities ) underscores the insincere nature of the charlatan introducing himself as possessor of powers he does not have.

Opera di Firenze. Cortile di palazzo Pitti. Prove generali dell’ opera “L’elisir d’amore”.

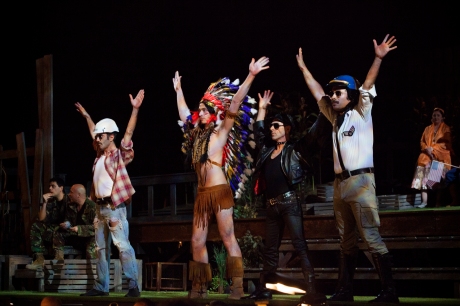

It must not be easy for a director to stage this opera while trying to say something new and personal. True, most modern productions justly move the location from the Basque Country indicated in the libretto to the flatlands of Lombardy, Donizetti’s native region. Gianandrea Gavazzeni famously asserted that the score of Elisir is redolent with the same scent as the earth of the countryside around Bergamo. The last Florentine production by Rosetta Cucchi had placed the opera in a performing arts school (think Fame) in an American inner city with sets and costumes reminiscent of Grease or Happy Days, which worked very well, provided one forgot or did not pay attention to the countless references to peasants and country life spread throughout the libretto. The new production by Pier Francesco Maestrini, with sets by Juan Guillermo Nova and costumes by Luca Dall’Alpi, is even more convincing because, while not leaving the new continent, he placed the action in a rural village surrounded by corn fields: a billboard announces that part of the action takes place at the “1970 Florence Fair”, and among the US locations by that name, the only one relatively closer to Route 66 (a road sing indicates the village is in its proximity) in the one in Arizona, with its varied humanity of cowboys, hippies, farmers with their pitchforks, Hare Krishnas, Mennonite milk-women, alternative artists, upper class ladies still wearing 1950s style clutching their pearls, and of course beautiful, provocative young women with platform sandals, skimpy shorts and shirts tied right under their breasts. Adina is the owner of a junk food restaurant and Nemorino is one of her employees, forced to spend most of Act I in a chicken costume to promote the greasy spoon’s fried wings. Belcore is the typical drill sergeant inciting his soldiers with one of the most famous running cadences, and will never remove his mirror sunglasses. Dulcamara is a snake oil salesman eerily looking like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler. Giannetta is the classic blond all-American girl, a Mena Suvari doppelganger. This production featured an endless series of gags, jokes, almost always funny and fitting: for example the keyboard played the “Tristan chord” when Dulcamara mentions Isolde in his Act II duet with Adina, and the trumpets hinted at “When the Saints go marching in” in some other part.

Opera di Firenze. Cortile di palazzo Pitti. Prove generali dell’ opera “L’elisir d’amore”.

Nothing but praise must be heaped upon the conductor, Alessandro D’Agostini. From the very first chords it was clear that he would be a key factor in this performance’s success, occasionally a martinet in rhythmic accents and insistence in clean phrasing but obtaining verve and clarity from the excellent orchestra of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. He did not ignore one of the cornerstones of a superior Donizetti performance, the rubatos. His conducting was rich with élan and languor, irony and passion, where elegance alternates to considerable stressing of the melodic abandonments. He seemed to find the right balance between the Janus Bifron nature of this opera that looks simultaneously at its eighteenth century roots and the unabashed Romanticism of many others moments. Extremely appreciated was his choice to perform the opera in its entirety with variations in the daccapos. Adriana Donadelli (Giannetta), a gorgeous young woman that can easily pass for a Texan beauty queen, with long legs, a Farrah Fawcett mane and the cheekbones of Jerry Hall, did however reveal a little vocal acerbity. The two lower voices acquitted themselves admirably: Marco Filippo Romano was a well sung Dulcamara, with precise patter, clear diction, a good legato (required in phrases like “ah, di patria il caldo affetto”) and a remarkable top (a secure high G in unison with the tenor at the end of their duet), but above all he was careful to eschew distasteful histrionics. Biagio Pizzuti displayed a rich, robust and virile baritone able to fill the grander phrases Donizetti allots his peacock sergeant, supported by a fine vocal production that enabled him to sing with suppleness and exhibit appreciable agility. Juan Francisco Gatell (Nemorino) did not start in good voice, causing some alarm with a cavatina that was not a model of homogeneous delivery. His performance decidedly improved all throughout the evening reaching good results in the most awaited moment, the Act II romanza, sung with a fine legato, a decent range of colours and intense pathos. But even before, the moment I personally consider the artistic peak of the opera “Adina, credimi”, interpreted with melancholy and a touch of feverishness, was heartbreaking. The queen of the party turned out to be Laura Giordano, a light-lyric soprano of moderate volume suited to the repertoire she has been performing; she has a warm, round timbre (which automatically sets her apart from the many soubrettes that monopolise this role) and a ringing, secure and easy top, as she repeatedly showed in the puntaturas: quite good was the two octave jump (C 6 – C 4). As for the agility, it was remarkable as demonstrated the triple-time cabaletta with its fast eight-note runs and spectacular variations.

Opera di Firenze. Cortile di palazzo Pitti. Prove generali dell’ opera “L’elisir d’amore”.

In conclusion, an Elisir well sung, well conducted, in a funny and entertaining production where nothing seemed to be left to chance and and – icing on the cake – staged in the courtyard of one of the most beautiful Italian palazzos: what more can one wish for?

Nicola Lischi

Photo credit: Pietro Paolini – Terre Project -Contrasto