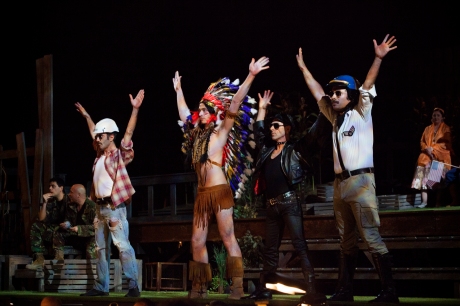

The first offering of the Opera di Firenze summer season, L’elisir d’amore and this Traviata have one thing in common: both are set in times and places quite remote from the ones indicated in the librettos, and – what’s more important – in locations known to almost everyone through endless movies and TV shows (the “South West” Elisir) or one of the most celebrated and iconic film of international cinema, Fellini’s La dolce vita, as in the case of the Verdi evergreen. Director Alfredo Corno places the action during the shooting of the movie, a classic case of captivating and engrossing ‘metatheatre’, even though, as it often happens in such cases of adaptations, some arm-twisting becomes necessary in order to force extraneous elements into the plot. After the projection in reverse of a poorly attended funeral procession during the Prelude, Act I opens in front of the Trevi Fountain, with our heroine dressed and coiffed as Anita Ekberg, making it immediately clear that they are on the set of the famed movie: Gastone is a paparazzo and the other interpreters and the chorus play other actors, stagehands, waiters, make up artists and so on. The audience soon realises that, if some scene are part of the script (the “Brindisi”, for instance), other, starting from Violetta’s sudden illness, are real life events. This prompts the first perplexities, because an actor falling in love with a colleague in the 1960s is not such a scandal as to cause his father to try to put a stop to the affaire; but in the finale of Act II the father is revealed to be an actor himself (playing Casanova, no less) and perhaps his attempt to shelter his son from a world he knows too well become more plausible. This finale takes place once again in a studio (Cinecittà studio number 5, where Fellini shot most if not all his movies), with a gathering of the most varied and eccentric Fellinesque humanity: the drag queens, the curvaceous, wide bosomed, mature women revealing too much skin (all played with fearless gusto by the choristers), the clergymen, and finally Gelsomina and “The Fool” tenderly comforting Violetta during the ensemble. Act III brings us in a dreary hospital room: Annina, who in the previous acts had appeared to me a sort of a manager or a secretary, is now a nun; Alfredo’s entrance is as unsentimental as it can be, keeping at a safe distance from Violetta, who manages somehow to pull him towards her; and Germont, a toy trumpet in his pocket, had clearly taken part to the Carnival celebrations. Paparazzo Gastone tries to take a photo of Violetta’s corpse. A gelid, aseptic death in the common indifference, with the exception of Suor Annina.

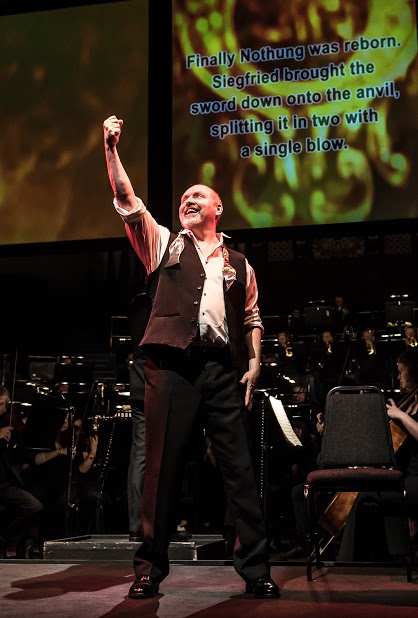

Firenze, Cortile di Palazzo Pitti, luglio 2016. Un momento della Prima della Traviata di Giuseppe Verdi, diretta da Fabrizio Maria Carminati, con la regia di Alfredo Corno e l’Orchestra ed il Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Florence, Pitti Palace Courtyard, July 2016. A moment of Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata, directed by Fabrizio Maria Carminati, conducted by Alfredo Corno and Orchestra and Chorus of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Fabrizio Maria Carminati’s reading of the score may not be to everyone’s liking, but I am sure that even his detractors cannot remain indifferent to his coherence and originality. A lean sound, linked to relatively fast tempos and a scarce interest in highlighting colours give birth to – in an almost black and white expressionism – pictures of intense tragedy, pervaded by a sort of gloomy fatalism. This is a society that, far from enjoying itself, plunges into an oppressive void, a society with no hope of rescue; the incessant hammering of the violins during the scene of Flora’s party turns into a true danse macabre. Absent is the feverish, neurotic wish for life that burns in so many Violettas: the Act I party is characterized only by fragility and weakness, overwhelmed by a relentless inexorability. Thus there is no rebellion or fight in Act II; she can only yield to something that had been foreboding since the very beginning.

Firenze, Cortile di Palazzo Pitti, luglio 2016. Un momento della Prima della Traviata di Giuseppe Verdi, diretta da Fabrizio Maria Carminati, con la regia di Alfredo Corno e l’Orchestra ed il Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Florence, Pitti Palace Courtyard, July 2016. A moment of Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata, directed by Fabrizio Maria Carminati, conducted by Alfredo Corno and Orchestra and Chorus of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Carminati’s conception was fully comprehended and followed by his leading lady. Francesca Dotto, a young soprano who has recently made headlines for taking part in the so-called “Valentino’s Traviata” at the Rome Opera House (which was Sofia Coppola’s first ever operatic production) does not have a particularly alluring or distinguished timbre, nor is it one of those voices that one recognises instantly, but it is a technically proficient instrument capable of doing full justice to virtually everything Verdi requires from her. She offered a charmingly fragile Violetta in the first act: the passagework was more than competent, with accurate descending roulades, and she was able to express the recklessness, if not the neurosis, suggested in “Sempre libera”. She sounded at ease at the top, where high Cs (including the repeated ones on “volar”) were secure and ringing, while the Ds flat of “Gioir!” sounded a little less confident. The optional E6 flat capping the cabaletta was very cautious and did not have that liberating power that it should when one chooses to include it. In the rest of he opera, her voice lacked the ideal body and warmth for the first scene in Act II, but she enacted it eloquently. “Dite alla giovine” was a measure of her art: she phrased it touchingly, with dignity and sorrow. “Amami, Alfredo” was sung very expansively but was perfectly proportioned. The final act had elegance. For example, “È tardi!” conveyed desperation without sounding vulgar or “veristic”. “Addio del passato”, fortunately sung in its entirety, was the peak of her performance. Despite the partial lack of desirable heft or seducing timbric quality, she chiselled the aria with a skilful game of chiaroscuros and delicate pianissimos, a further proof of her innate musicianship. Matteo Lippi (Alfredo), a pupil of Mirella Freni, is a another thirty-something tenor just a few years into his career. My impression is substantially positive, as he seems to be a tenor with a good knowledge of the mechanism of a correct vocal production; he is able to sing ‘on the breath’, to modulate an instrument gifted with a remarkable volume and a pleasant timbre, even though he seems to recur to a nasal sound too often, probably thinking this helps the ascent towards the top register. His looking too cold and staid on stage was probably due to the director’s concept of his character. Simone Del Savio was a fine Germont: his baritone is quite sizeable as well as a bit monolithic and not particularly nuanced. He also proved to possess a good schooling, and was able to perform technical feats such as skipping a breath (in the first strophe of “Di Provenza”) in “Dio mi guidò, Dio mi guidò” after the high F, reaching the climatic G flat without a break. Among the secondary parts the Flora of Ana Victoria Pitts (already appreciated in much bigger assignments) stood out with her appealing mezzo-soprano and her ability to perform the gruppetti of “Il lupo perde il pelo…” with precision. The cast also included Patrick Kabongo Mubenga, a tenor with a nice timbre and a less than acceptable diction, Byongick Cho, a particularly fearsome Douphol, Pavlo Balakin (Grenvil), Matteo Loi (Obigny), Eunhee Kim (a good singer wasted as Annina), Leonardo Melani (Giuseppe), Nicolò Ayroldi (Flora’s servant, also heard in more rewarding roles) and Nicola Lisanti (Commissionario). The Chorus and the Orchestra of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino were exquisite, as always.

Firenze, Cortile di Palazzo Pitti, luglio 2016. Un momento della Prima della Traviata di Giuseppe Verdi, diretta da Fabrizio Maria Carminati, con la regia di Alfredo Corno e l’Orchestra ed il Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Florence, Pitti Palace Courtyard, July 2016. A moment of Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata, directed by Fabrizio Maria Carminati, conducted by Alfredo Corno and Orchestra and Chorus of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Despite some confusing moments, it is legitimate to describe this Traviata as an ultimately successful production, with an accomplished cast and the technically flawless, whipping, I daresay appropriately cruel conducting of Fabrizio Maria Carminati.

Nicola Lischi

Photo credit: Simone Donati-Terra Project-Contrast